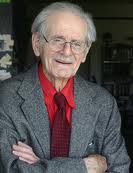

Norman Corwin 1910 – 2011

Having a break with my third morning coffee, I scanned through the Los Angeles Times. Flipping pages rapidly to go back to work, I stopped at Norman Corwin’s obituary. “Wow, he had crossed the Centenarians’ Marathon line, working and teaching to the end,” I said to myself.

Corwin was dubbed “radio’s poet laureate.” Ray Bradbury defined him as “the best radio-producer-director in the whole history of radio.”

When our daughter Gabby was nine years old we decided to have a creative summer vacation at ISOMATA (Idyllwild School of Music and the Arts, now called Idyllwild Arts Academy, up in California’s San Jacinto Mountains.) Gabby would be entertained learning crafts and dancing in the woods; Ruth would develop her drawing skills with Joseph Mugnaini, a master artist and teacher; and I would learn creative writing with…Norman Corwin.

The daily classes started at 8:00 AM sharp. Our meetings were held at a log cabin surrounded by trees and boulders. The room was mostly filled with a long table that left little space to sit between it and the walls. Mornings were chilly, so the tightness helped to warm up and gave us an intimate atmosphere.

Corwin was there before anyone arrived. He wore a sport jacket, a sweater and a tie. He seemed to carry well his late seventies. On the first class he asked for a self-introduction. Four of my classmates were journalists, two were fiction writers and one was a historian. When my turn came, I felt embarrassed at being in the company of professionals.

“I’m an architect,” I said.

“From?” said Corwin.

“I grew up in Argentina, lived in Italy and Israel, and now I live in L.A.,” I said. “I like to write, but I’m not a writer. English is my fourth language. Given the company, I’m not sure I’m at the right place.”

“My goodness,” Corwin said. “You have a goldmine. Are you aware of it? This is a right place for you. Take it as an adventure.”

We had to write one story every day. Corwin would give us an assignment, a choice between two single words, such as “apple” and “fireplace.” Solitary writing started after lunch, in the woods. It continued after diner, until midnight. Critiques restarted the next morning.

Corwin’s awareness was high on multiple aspects: politics, art, literature, cinema, history, design, sports, the media and…architecture. In one of his many books, most of which you may read today as if they were written yesterday, he wrote, referring to monumental architecture:

“vastness is oppressive when thrust on human senses and capacities. The pyramids of antiquity, the mammoth heads of Abu Simbel and Mount Rushmore, are meant to be seen from afar, not touched.”

Corwin’s sharp eye and great writing continue to cast light on architecture.

(1)

Architecture Awareness

Architecture Awareness